What Were Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communists Doing Around the Time of the Cairo Conference?

By Yang Jianli, published: September 1, 2015 www.chinachange.org

|

| CAIRO CONFERENCE, 1943. VIA @HEGUISEN |

“At the time of the Cairo Conference, although the US military had already gained the upper hand in the Pacific and was actively planning an Allied invasion of Europe, and despite the first glimmerings of hope for an Allied victory over Germany, Italy and Japan, another threat was already taking shape, this time within Allied ranks: it would grow to become the greatest and most persistent threat to global peace in the post-war era.”

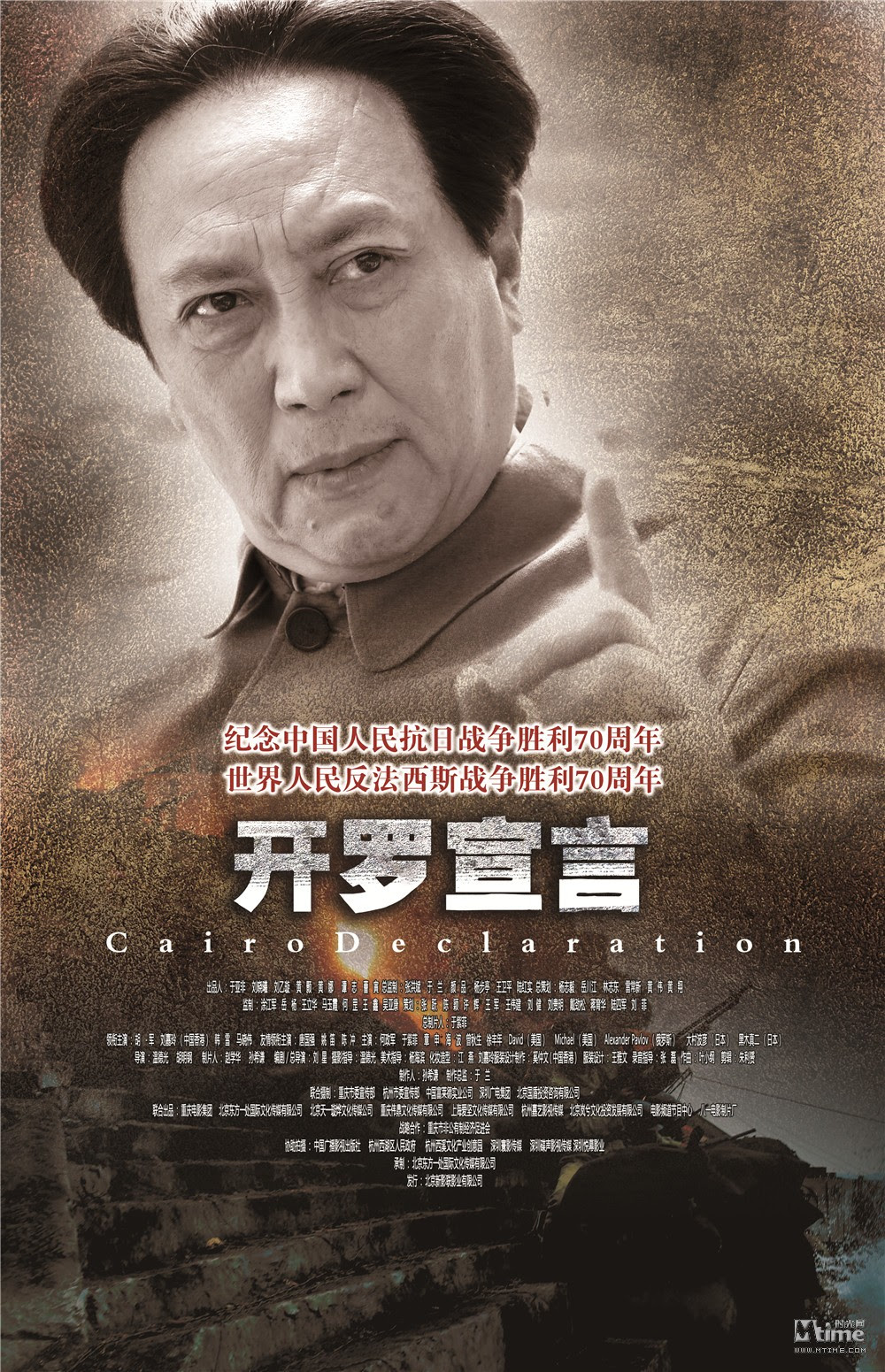

On the eve of the 70th anniversary celebration of the victory over Japan in World War II, The Cairo Declaration – a so-called “historical epic” produced by the August First Film Studio – has managed to cause a public outcry even before its theatrical release. The reason for the outcry is that publicity posters for the film feature Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong front and center, despite the fact that he had nothing to do with the Cairo Conference. For a time, the poster became an object of public ridicule and Internet spoofs by Chinese citizens, overseas Chinese and the international public. Wanton misrepresentation and distorted history are par for the course for the Chinese Communist Party and its propaganda machine, but in this article, I would like to raise and hopefully answer the following question: At the time of the Cairo Declaration, exactly where was Mao Zedong and what was he doing? Understanding the answer will not only clarify an historical point of fact, but also give us a fuller understanding of the prevailing domestic and international situation at the time, and maybe even help us to interpret the critical problems China faced in the years after the Cairo Declaration.

The Cairo Conference that took place between November 22-26, 1943, was a gathering of the leaders of the United States, Britain and China: Roosevelt, Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek. At that time, Mao Zedong was in Yan’an in northwest China, doing things that would alter the future of China, and indeed the future of the world, every bit as much as Chiang Kai-shek would.

We know that when the Red Army arrived in northern Shaanxi after the Long March, it numbered fewer than 30,000 troops, and by the time of the Xi’an Incident (西安事变) of 1936, it had had recovered to about 50,000 troops. After the Xi’an Incident, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) won not only legal recognition of its status, but also funding from the Republic of China central government, and its fighting strength rapidly improved. By late 1937, the Communist-led Eighth Route Army numbered over 80,000, and the incorporation of guerrilla forces south of the Yangtze into the Communist-led New Fourth Army expanded that army unit to 12,000. From 1937 to 1940, CCP-led military forces increased by fifty to one hundred percent annually. In August 1940, the Eighth Route Army launched the One Hundred Regiments Offensive (百团大战) against Japan; in October 1940, skirmishes between New Fourth Army and Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang, or KMT) troops led to the Battle of Huangqiao (黄桥战役), in which the New Fourth Army wiped out over 10,000 KMT troops. These two battles gave the world a new appreciation of the rapidly developing fighting prowess of Chinese Communist forces.

We know that when the Red Army arrived in northern Shaanxi after the Long March, it numbered fewer than 30,000 troops, and by the time of the Xi’an Incident (西安事变) of 1936, it had had recovered to about 50,000 troops. After the Xi’an Incident, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) won not only legal recognition of its status, but also funding from the Republic of China central government, and its fighting strength rapidly improved. By late 1937, the Communist-led Eighth Route Army numbered over 80,000, and the incorporation of guerrilla forces south of the Yangtze into the Communist-led New Fourth Army expanded that army unit to 12,000. From 1937 to 1940, CCP-led military forces increased by fifty to one hundred percent annually. In August 1940, the Eighth Route Army launched the One Hundred Regiments Offensive (百团大战) against Japan; in October 1940, skirmishes between New Fourth Army and Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang, or KMT) troops led to the Battle of Huangqiao (黄桥战役), in which the New Fourth Army wiped out over 10,000 KMT troops. These two battles gave the world a new appreciation of the rapidly developing fighting prowess of Chinese Communist forces.Throughout the war, with the notable exception of the Hundred Regiments Offensive, Communist forces rarely engaged in large-scale battles with the Japanese army. The well-known statement that the Chinese Communists spent “10% of their time fighting [the Japanese], 20% in skirmishes [with the Nationalists], and 70% expanding [their political influence]” is borne out by a close examination of CCP wartime history. As Communist forces grew in military strength, skirmishes between Communist and Nationalist government forces became more frequent. This eventually led to the Wannan Incident of 1941 (皖南事变), in which the New Fourth Army suffered great losses. CCP troop losses in the Wannan Incident and the Hundred Regiments Offensive convinced Mao Zedong that he needed to strengthen his authority over the military.

In the past, the Eighth Route Army’s frontline leader Peng Dehuai and the New Fourth Army’s political commissar and de-facto leader Xiang Ying were not sufficiently obedient to Mao, but Mao understood that the CCP’s objective was not to fight the Japanese, but to allow the Nationalists and the Japanese to battle it out and destroy each other, thus allowing the CCP to step in and seize power after the war. This had always been Mao‘s primary concern. Moreover, by this time the Japanese had already halted their westward advance, and the Xi’an line was no longer under threat from the Japanese, allowing Mao to concentrate his efforts on military expansion, on the one hand, and on inner-party power struggles, on the other.

Aiming to rid the CCP of dissenting opinions, Mao launched his Yan’an Rectification Movement (延安整风运动) in May 1941; the movement continued unabated until the war ended in the summer of 1945. During this period, the CCP and the Japanese did not engage in any major clashes or battles. On the contrary, there are strong suspicions that, during this same period, CCP intelligence agents maintained friendly contacts and traded information with the intelligence organizations of local Japanese-backed puppet regimes.

As Roosevelt, Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek were meeting in Cairo, Mao‘s Yan’an Rectification movement was in full swing. From September 1943 to April 1944, the CCP Central General Study Committee held a series of rectification meetings during which Wang Ming, Zhou Enlai, Zhang Wentian, Qin Bangxian, and other party leaders accused of “dogmatism” and other offenses were forced to engage in self-criticisms and soul-searching, thus paving the way for Mao Zedong to seize full power for himself. During these meetings, Peng Dehuai also came in for severe censure for not securing the approval of Party central when he launched the Hundred Regiments Offensive, which revealed to the world the true military strength of Chinese Communist troops. Although Peng Dehuai refused to grovel before Mao Zedong as some of the other leaders did, in the end, he had no choice but to make a self-criticism too.

In retrospect, we can see that while the Allied and Axis powers were suffering terrible losses fighting each other during World War II (this includes the war between Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union), Mao Zedong spent the period from 1941 onward enjoying the protection of Shanxi warlord Yan Xishan to the east, and Xinjiang warlord Sheng Shicai to the west, shouting patriotic anti-Japanese slogans, periodically requesting handouts of grain tax from the Chinese Republican central government tax coffers, and transforming Yan’an into a Communist Utopia in the midst of a warzone. In Yan’an, he was free to indulge his own whims in remaking CCP military and political leadership, carrying out a brutally-thorough brainwashing campaign of the armed forces and political cadres, and becoming the first CCP leader in history to exercise full control over both the military and the Party.

This level of transformation and centralization would have been impossible for Chiang Kai-shek, who had his hands full battling the Japanese. Therefore, when the Chinese Civil War broke out a few years later, Chiang Kai-shek was no match for Mao Zedong, who enjoyed an unprecedented level of military control.

Roosevelt, Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek were clearly unaware that while they were meeting in Cairo to secure peace for all humanity, Mao Zedong was hidden away in his Yan’an oasis making preparations for the coming large-scale civil war. The reason Maocould lay low in Yan’an was because Chiang Kai-shek was busy at the front, fighting Japanese Imperial Army troops tooth and nail; because the U.S. Navy was crisscrossing the vast Pacific Ocean, wresting control of one after another small island from the Japanese; and because American, British and Chinese Nationalist troops were engaged in bloody combat against the Japanese all over South Asia. The purpose of the Cairo Conference was to cement this alliance, and to expand the scope of their wartime cooperation after the conference was over. Thanks to the hard work of the world leaders who did actually attend the Cairo Conference, Mao Zedong had the leisure to remain in Yan’an furthering his Rectification Movement, watching operas, dancing and wooing.

Far from Yan’an, in the various CCP “Anti-Japanese Base Areas,” Communist troops and local militias did their best to avoid direct military confrontation with the Japanese, but they engaged in skirmishes with Nationalist troops and took every opportunity to seize more of their weapons and territory. For example, former CCP Defense Minister Zhang Aiping recalls that when he was operating behind enemy lines in Jiangsu as Deputy Commander of the CCP’s New Fourth Army, Third Division, he received a message sent by Han Deqin (the Chinese Nationalist Deputy Commander of the Suzhou-Shandong Military Region, and distinguished commander during the Battle of Tai’erzhuang in 1938) asking for permission to withdraw his men temporarily to an area near the Cai Bridge in Huai’an, because his men had suffered such heavy casualties fighting the Japanese in northern Jiangsu. Falsely claiming that the bridge was too narrow to provide any real safety, Zhang Aiping instead suggested that Han Deqin and his troops retreat to the shore of Lake Hongze, where the CCP New Fourth Army, Fourth Division, had established a line of defense. As a result, when Han Deqin and his men arrived at Lake Hongze, they were met by a surprise attack from the New Fourth Army, Fourth Division, under the command of Peng Xuefeng (whom Zhang Aiping had notified by telegram beforehand). Many of Han Qinde’s men were killed, their weapons and ammunition taken as spoils, and Han Qinde himself taken prisoner.

Let us leave Yan’an for a moment, and take a peek at Mao Zedong‘s political patron, Joseph Stalin. We know that Stalin declined to attend the Cairo Conference because he was unwilling to meet with Chiang Kai-shek. In order for these four Allied nations (the U.S., U.S.S.R., Britain and China) to coordinate their wartime strategy, the planned four-party conference had to be divided into two parts: the Cairo Conference and the Tehran Conference. After the meeting in Cairo concluded, Roosevelt and Churchill headed for Tehran to meet separately with Stalin. At the Yalta Conference chaired by Stalin in Soviet territory one year later, China’s highest-ranking official Chiang Kai-shek was not even invited to attend, despite the fact that the U.S.S.R. and the Republic of China had established formal diplomatic relations.

Therefore, at the time of the Cairo Conference, although the US military had already gained the upper hand in the Pacific and was actively planning an Allied invasion of Europe, and despite the first glimmerings of hope for an Allied victory over Germany, Italy and Japan, another threat was already taking shape, this time within Allied ranks: it would grow to become the greatest and most persistent threat to global peace in the post-war era. As subsequent history would prove, far more people would die under the Communist tyranny of Stalin and Mao than under the fascist tyranny of the Axis powers. When it came to provoking conflict or warfare to suit his own interests and ambitions, Mao was clearly a cut above the rest. The leaders of the Western world, particularly President Roosevelt, severely underestimated the rise of Communism as both a political force and a political threat. This was due in part to Stalin’s apparent adaptability and Mao Zedong‘s clever ruse of filling the Xinhua Daily and other official Communist newspapers with slogans of democracy and freedom.

Discussions at the Cairo Conference mainly focused on issues related to the independence and territorial integrity of China, Japan, Korea and the nations of Southeast Asia. The postwar peace more or less adhered to the demands set out in the Cairo Declaration – the independence of Korea, Manchuria and Taiwan, and the return of the Penghu Islands to the Republic of China – although both the Chinese mainland and the Korean peninsula would soon be engulfed by more fighting. By early 1945, four years into the Yan’an Rectification Movement he had launched, Mao realized that Japan’s defeat would come about earlier than he had anticipated, so he hastily wrapped up the rectification movement, issued a mea culpa to those who had been targeted for rectification, and began preparing for civil war with the Chinese Nationalists.

Among the western nations, World War II was seen as a war to defend world peace and human freedom. But in the triangular relationship between the Allies, the Axis and the U.S.S.R. (and its junior partners, Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party), the western world was devoting so much of its energy to dealing with West Germany, Italy and Japan, that it neglected to remain sufficiently vigilant against Communism, which spread rapidly in the absence of any organized opposition. This is a point on which we should reflect today, as we commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Even the United Nations, one of the most positive outcomes of the Second World War, has not proven an effective defender of freedom and human rights around the world; in this sense, it is not unlike its predecessor, the League of Nations. Today, the Communist nations of Asia that emerged in the wake of the Second World War continue to suffer from numerous human rights violations and the failure to protect the basic rights and freedoms of their citizens. In this sense, the World War II objective of defeating fascism remains incomplete.

There is a Chinese proverb that warns of the danger of pursuing one’s aims so single-mindedly that one remains blind to the larger dangers: “The mantis stalking the cicada does not notice the lurking finch.” If Roosevelt, Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek-so intent on fighting the Axis powers-were the mantis stalking the cicada, then Mao Zedong-with his long-contemplated scheme to seize the whole of China and “liberate” all humanity-was certainly the finch, waiting to pounce at the first opportune moment. That point is essential to any accurate depiction of the geopolitical landscape during World War II. Moreover, were it not for Mao Zedong, there would be no death-and-disaster-ridden Red China, nor the Korean War, nor the Vietnam War, nor the Cambodian Khmer Rouge.

In late 1943, when most of humanity was endeavoring to end the Second World War, it was easy to overlook that irrepressible time traveler, Mao Zedong. Looking back on those war years, one might forget that Mao Zedong even existed, for his contributions to the war effort were minimal. But Mao was not idle during this period. Let us remember this, and trust that today’s World War II historians will never again neglect the fact ofMao‘s existence in late 1943. We should thank the makers of The Cairo Declaration, for it was they who dragged Mao Zedong, in all his false glory, from his cave in Yan’an and placed him squarely where he belongs: in the midst of a true picture of the Second World War, a canvas on which we can reflect and remember.

August 27, 2015

(This article was slightly abridged, edited, and translated by China Change, with the consent of the author.)